TL;DR

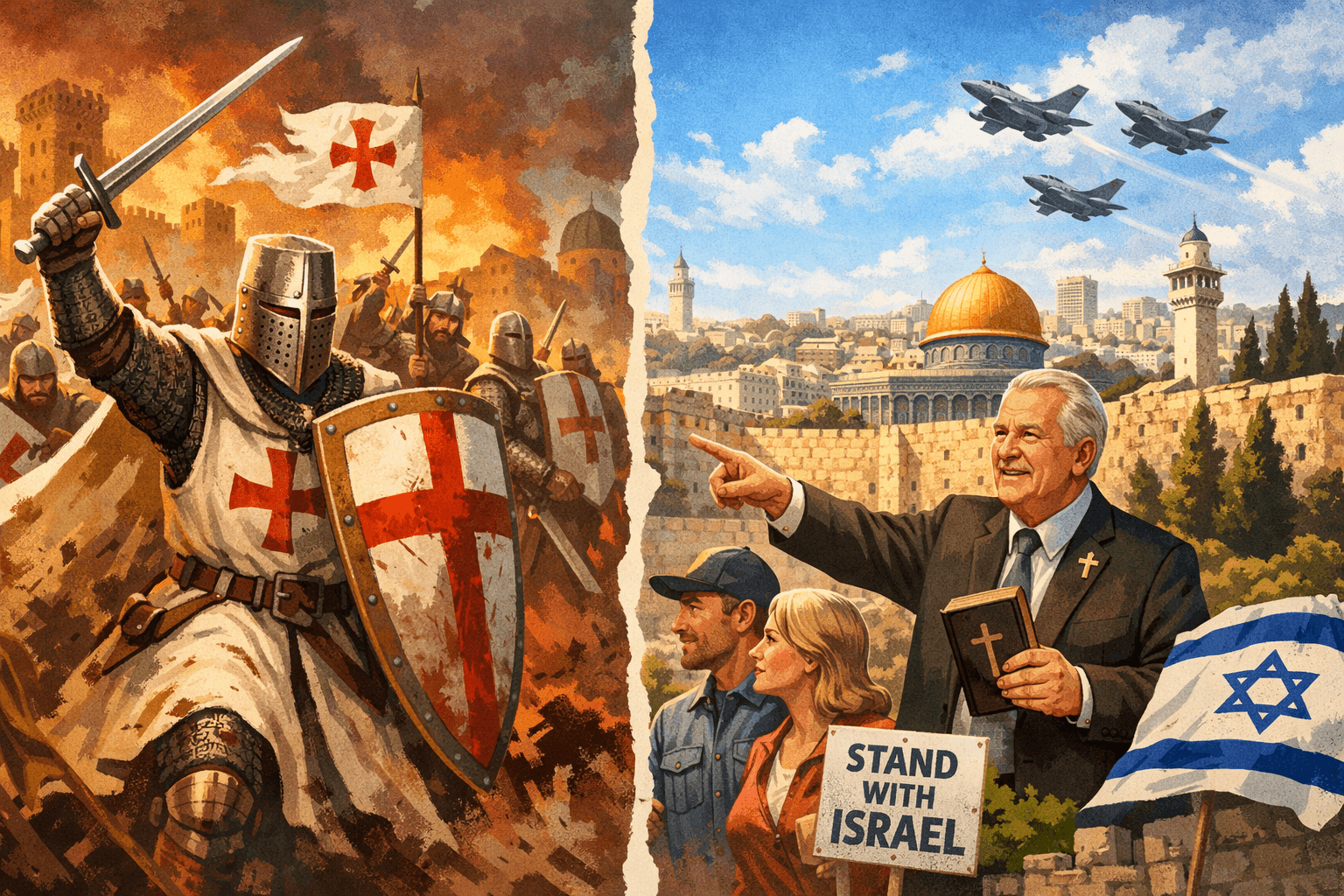

The theological moves that justified the Crusades—sacralising territory, demonising enemies, silencing dissent—reappear in modern Christian Zionism. This essay traces the dangerous pattern of transforming political positions into divine mandates, then and now.

On 14 May 2018, as the United States opened its embassy in Jerusalem, Pastor Robert Jeffress delivered the opening prayer. "We thank you every day that you have given us a president who boldly stands on the right side of history, but more importantly, stands on the right side of you, O God, when it comes to Israel," he prayed. Meanwhile, 60 kilometres away in Gaza, Israeli forces killed 58 Palestinians and wounded thousands more during protests against the embassy move. The juxtaposition was stark: a political decision framed as divine alignment, criticism of it implicitly cast as opposition to God's will, and violent consequences unfolding in real time.

This incident exemplifies a pattern worth examining: the transformation of contested geopolitical realities into theological certainties. When political positions about modern Israel become matters of religious orthodoxy—when supporting specific policies is equated with faithfulness to God—we witness a rhetorical and theological move with deep historical precedent. The most instructive parallel may be the Crusades, where similar dynamics played out with catastrophic consequences.

This essay argues that contemporary Christian Zionism—particularly in its more theologically deterministic forms—employs a structure of reasoning strikingly similar to Crusader theology. Both movements take complex political situations and reframe them as divine imperatives. Both treat specific territorial claims as non-negotiable matters of faith. Both struggle to permit legitimate dissent without construing it as heresy or unfaithfulness. And both risk a dangerous form of idolatry: elevating nation and land to a status that competes with Christ himself.

This is not an argument about moral equivalence. The Crusades were explicitly military campaigns of conquest; modern Christian Zionism primarily involves political and financial support for an existing nation-state. The violence, the agency, and the historical contexts differ substantially. Nor is this a blanket condemnation of all Christian engagement with Israel or Jewish-Christian relations. There are legitimate historical, political, and even theological reasons for Christians to care about Israel's existence and security.

Rather, this is an argument about a particular mode of theological reasoning—one that transforms prudential political judgements into divine mandates, that treats debatable positions as revealed truth, and that thereby forecloses the possibility of faithful disagreement. Understanding this pattern matters because it continues to shape both foreign policy and Christian witness today.

How the Crusades Were Theologised

When Pope Urban II stood before the Council of Clermont in November 1095, he did not merely propose a military campaign. He announced a holy obligation. According to multiple chroniclers, Urban described the alleged desecration of Jerusalem's holy sites, the supposed persecution of Eastern Christians, and the pollution of sacred geography by Muslim presence. But crucially, he framed military intervention not as one possible response among many, but as "a task enjoined on the faithful by God Himself."[^3] The message was echoed in the assembled crowd's cries of "Deus lo volt!"—"God wills it!"—which became the Crusaders' battle cry.[^4]

[^3]: Christopher Tyerman, Fighting for Christendom: Holy War and the Crusades (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 19.

[^4]: Tyerman, Fighting for Christendom, 19.

The theological architecture supporting the Crusades rested on several key pillars. First was the sanctification of specific territory. Jerusalem was not simply historically significant or strategically important; it was intrinsically holy, the navel of the world, the site of Christ's death and resurrection. Its "occupation" by Muslims was therefore not a geopolitical reality to be negotiated but a cosmic offence to be rectified. Bernard of Clairvaux, preaching the Second Crusade, described the land itself as crying out for Christian liberation.

Crucially, crusading was an inherently spatial practice. Medieval sources often described crusades as a "military monastery on the move"—the journey itself was a penitential act tied to the physical site of Jerusalem. The land wasn't merely a destination; it was sacramental. By travelling to and fighting for Jerusalem, crusaders participated in sacred geography, quite literally walking in Christ's footsteps. This meant the city's physical location mattered theologically. One couldn't simply spiritualise Jerusalem or treat it as metaphor. The dirt, stones, and territorial boundaries became invested with cosmic significance.

This sacralisation transformed negotiable political borders into non-negotiable divine boundaries. When territory becomes not just important but cosmologically necessary—when borders are divine boundaries rather than political ones—normal diplomatic negotiation becomes theological betrayal. To suggest that Muslims might have legitimate claims to Jerusalem, or that Christians might share the city, was to misunderstand the fundamental nature of sacred space. The land had been promised by God, consecrated by Christ's presence, and defiled by infidel occupation. Any resolution except total Christian control was unthinkable.

Importantly, "crusade thought or ideology was not laid out at the Council of Clermont in 1095 and set in stone thereafter."[^10] What crusading meant evolved continually. But across this development, certain patterns persisted: the treatment of complex political situations as theological certainties, the elevation of land to sacred status through mechanisms of sacralisation, and the framing of dissent as unfaithfulness.

[^10]: Megan Cassidy-Welch, Crusades and Violence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023), 15.

Second was the construction of religious enemies as not merely adversaries but as agents of evil opposing God's purposes. Muslims were "infidels," "pagans," and "the spawn of Satan." This wasn't ethnic prejudice dressed up in religious language (though it certainly became that); it was a theological category. To fight Muslims in the Holy Land was to fight on God's behalf against those who opposed him. The conflict was cosmological before it was political. As crusading rhetoric put it simply: "Christians are right and pagans are wrong."

This Manichaean worldview—a cosmic battle between absolute good and absolute evil—proved remarkably durable. It reappears in modern Christian Zionist rhetoric, albeit with different enemies. Tim LaHaye's Left Behind series popularised the concept of the "humanist tribulation," wherein liberal humanists, secular elites, and international organisations are portrayed as agents of a "deep-state" conspiracy paving the way for the Antichrist. Like medieval Muslims, these enemies aren't simply politically mistaken; they're spiritually aligned against God's purposes, making opposition to them an existential spiritual struggle.

This pattern connects directly to War on Terror rhetoric and broader Christian nationalist discourse. When political opponents become cosmologically significant—when disagreement about tax policy or Middle East diplomacy is reframed as choosing sides in a spiritual war—the possibility of compromise evaporates. You cannot negotiate with agents of evil; you can only defeat them. The theological category does the work of delegitimising ordinary political disagreement by elevating it to cosmic stakes.

Third was the promise of spiritual reward for participation. Urban II offered plenary indulgence—full remission of sins—to those who took up the cross. Dying in the Crusade was effectively martyrdom, a direct path to salvation.[^5] This transformed military service into salvific activity, collapsing the distinction between political action and religious devotion.

The theological architecture became even more explicit with subsequent crusades. Bernard of Clairvaux (d. 1153), "chief propagandist and recruiting agent for the Second Crusade" and "one of the most influential interpreters of Christian spirituality of the entire Middle Ages," radically reinterpreted New Testament passages to justify holy war.[^6] The Apostle Paul had used military metaphor spiritually: "We do not war after the flesh: for the weapons of our warfare are not carnal" (2 Corinthians 10:3-4). In Ephesians, Paul wrote of spiritual armour: "Put on the whole armour of God...For we wrestle not against flesh and blood" (Ephesians 6:11-12).

Bernard redirected Paul's spiritual warfare into literal combat. In his tract welcoming the founding of the Templars, he wrote of "a new sort of knighthood...fighting indefatigably a double fight against flesh and blood as well as against the immaterial forces of evil in the skies." He urged: "So forward in safety, knights, and with undaunted souls drive off the enemies of the Cross of Christ."[^7] What Paul meant as metaphor for spiritual struggle, Bernard transformed into justification for physical warfare. As Tyerman notes, this seemed to contradict Christ's own words: "Put up again thy sword...all they that take the sword shall perish with the sword" (Matthew 26:52-54).[^8]

[^5]: On indulgences and crusading, see Tyerman, Fighting for Christendom, 125-154.

[^6]: Tyerman, Fighting for Christendom, 96.

[^7]: Bernard of Clairvaux, quoted in Tyerman, Fighting for Christendom, 97.

[^8]: Tyerman, Fighting for Christendom, 96.

Fourth, and perhaps most relevant to our analysis, was the delegitimisation of dissent. Those who questioned the Crusades' legitimacy, who raised concerns about their violence or their theological justification, found themselves accused of lacking faith or opposing God's revealed will. When the monk Ralph Niger dared to criticise the Third Crusade in his 1187-88 treatise De re militari, arguing that Christ's kingdom was not of this world and that forced conversion contradicted the gospel, his work represented a rare but marginalised voice of dissent.[^1] The theologisation of the Crusades made scepticism itself suspect.

[^1]: John D. Cotts, "Earthly Kings, Heavenly Jerusalem: Ralph Niger's Political Exegesis and the Third Crusade," The Haskins Society Journal 30 (2018): 159-176.

None of this emerged from straightforward biblical exegesis. Jesus never commanded the recapture of Jerusalem. The apostles never suggested military campaigns to secure holy sites. Instead, Crusader theology wove together selective Old Testament passages about land conquest, New Testament metaphors about spiritual warfare, patristic speculation about sacred geography, and contemporary political anxieties into a comprehensive justification for war. The result was presented not as one possible interpretation but as divine mandate.

Yet crusading was "born and conducted in controversy" and "provoked criticism as an overt embrace of physical war as an act of penance."[^9] From the beginning, some recognised the theological problems. Ralph Niger, in his treatise De re militari (1187-88), questioned whether God wished the faithful to end Muslim domination of the holy places, arguing that Christ's kingdom was "not of this world" and that forced conversion contradicted the gospel.[^1] Isaac of Stella (Isaac de l'Étoile), a Cistercian abbot, warned against confusing the earthly Jerusalem with the heavenly Jerusalem, and took a strong critical stance against the new military orders being founded to force conversion at sword-point.[^2] But these voices were drowned out by the thundering certainty of crusading preachers who insisted that God's will was clear and questioning it was unfaithfulness.

[^9]: Tyerman, Fighting for Christendom, 16.

[^2]: On Isaac's criticism of military orders, see the discussion in "Isaac de l'Étoile and Adam de Perseigne," The Amalrician Heresy (blog), https://theamalricianheresy.wordpress.com/isaac-de-l-etoile-and-adam-de-perseigne/. Isaac called these orders "dreadful" and predicted their methods would later be used to persecute Christians.

The Crusades, of course, failed by their own standards. Jerusalem changed hands multiple times. Crusader states collapsed. The Islamic world was not converted. And the legacy was one of enduring bitterness, atrocity, and the poisoning of Christian-Muslim relations for centuries. Yet the theological pattern—transforming political goals into divine mandates, treating territory as intrinsically sacred, delegitimising dissent as unfaithfulness—would recur.

How Israel Is Theologised Today

Contemporary Christian Zionism is not monolithic. It encompasses various theological traditions—dispensationalist evangelicals, covenant theologians, some charismatic movements—with meaningfully different emphases and arguments. But across these variations runs a common thread: the claim that supporting the modern state of Israel is not merely a defensible political position but a theological necessity, grounded in Scripture and required by faithfulness to God.

The most influential form is dispensationalist Christian Zionism, which emerged from 19th-century premillennial theology and was systematised and popularised through the Scofield Reference Bible (first published 1909, revised 1967). C.I. Scofield's achievement was to take disparate strands of premillennial thought and weave them into a coherent system accessible to ordinary believers. Through cross-references, notes, and section headings embedded directly in the biblical text, Scofield provided what believers experienced as a "God's-eye view" of history—a clear, linear narrative stretching from creation to the end times, with contemporary events positioned precisely within God's prophetic timetable.

The Scofield Bible functioned as a standardising work that transformed new premillennialism into a cohesive religious identity for millions of Americans. By the early 20th century, it had become the most widely used study Bible among evangelicals, making Scofield's interpretive framework seem synonymous with Scripture itself. Readers didn't experience themselves as reading Scofield's interpretation of prophecy; they experienced themselves as reading what the Bible plainly says about prophecy.

This dynamic closely parallels how twelfth-century chroniclers retroactively "invented" the First Crusade as a unified theological event. The actual 1096-1099 expeditions were messy, confused, politically motivated, and theologically ambiguous. But chroniclers like Robert the Monk and Fulcher of Chartres imposed narrative coherence, stripping away political messiness in favour of theological clarity. They provided a script that made participants feel they were part of foreordained sacred history rather than contingent political violence. Similarly, Scofield took the ambiguous, contested terrain of biblical prophecy and provided a script that made twentieth-century evangelicals feel they were reading God's blueprint for history.

This theology divides history into distinct "dispensations" and maintains a sharp distinction between God's dealings with Israel and the church—what might be called a radical distinction between God's two peoples. As early dispensationalist John Nelson Darby wrote in 1839, "The church and the people of Israel are each respectively the centres of the heavenly glory and of the earthly glory, each of them has a sphere which is proper to itself."[^24] Israel has earthly promises, including literal land; the church has heavenly promises. Crucially, Scofield and his successors interpreted Old Testament land promises to Abraham and his descendants as unconditional, eternal, and unfulfilled—requiring the restoration of Israel to the land as a prerequisite for Christ's return.

[^24]: John Nelson Darby, quoted in Hummel and Noll, Rise and Fall of Dispensationalism, 24.

Passages like Genesis 12:3 ("I will bless those who bless you, and whoever curses you I will curse") are read as applying directly to the modern nation-state of Israel. John Hagee, founder of Christians United for Israel (CUFI), exemplifies this approach. He bases his "expectations of divine blessings and curses on his reading of Genesis 12:3," teaching that supporting Israel brings God's blessing while criticising it invites divine curse.[^15] As he stated: "For twenty-five, almost twenty-six years now, I have been pounding the evangelical community over television. The Bible is a very pro-Israel book. And if a Christian admits, 'I believe the Bible,' I can make him a pro-Israel supporter or they will have to denounce their faith."[^16] Supporting Israel becomes not merely a defensible political position but a test of biblical fidelity.

The 1967 New Scofield Reference Bible made this connection even more explicit. A new note to Genesis 12:1-4 "integrated the Holocaust and the creation of the State of Israel in 1948 into the Bible's prophetic foreknowledge," clarifying that God's promise to curse those who curse Abraham "was 'a warning literally fulfilled in the history of Israel's persecutions. It has invariably fared ill with the people who have persecuted the Jew—well with those who have protected him. For a nation to commit the sin of antisemitism brings inevitable judgment.'"[^17]

[^15]: Daniel Hummel and Mark A. Noll, The Rise and Fall of Dispensationalism: How the Evangelical Battle over the End Times Shaped a Nation (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2023), 334.

[^16]: Quoted in Terence Donaldson and Stephen Sizer, "Who Is Israel? The Hermeneutical Confusion of Christian Zionism," in The Last Days of Dispensationalism: A Scholarly Critique of Popular Misconceptions, ed. Marvin R. Wilson (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2010), 49.

[^17]: Hummel and Noll, Rise and Fall of Dispensationalism, 281-282.

Similarly, texts like Zechariah 12:3 ("On that day, when all the nations of the earth are gathered against her, I will make Jerusalem an immovable rock for all the nations") are read as prophecies about contemporary geopolitics. International criticism of Israeli policies is thereby not political disagreement but the fulfilment of prophecy—nations arraying themselves against God's chosen. This interpretive move renders such criticism not merely wrong but cosmologically significant, a sign of end-times apostasy.

Covenant theology, while different in structure, can lead to similar practical conclusions. Some Reformed theologians argue that God's covenant with Abraham remains in force, that the physical land promises have not been annulled by Christ, and that Christians therefore have an obligation to support Jewish claims to the territory. While generally more nuanced than dispensationalism—many covenant theologians emphasise spiritual fulfilment and reject rigid eschatological timetables—the net effect can still be the theologisation of territorial politics.

These theological convictions translate into concrete political and financial support. Christian Zionist organisations in the United States, such as Christians United for Israel (CUFI), founded by John Hagee in 2006, claim millions of members (over 11 million by 2022) and exercise significant lobbying influence.[^18] They advocate for unconditional U.S. support for Israeli government policies, oppose any territorial concessions in peace negotiations, and frame such positions not as foreign policy preferences but as biblical mandates.

[^18]: Hummel and Noll, Rise and Fall of Dispensationalism, 333-334.

Financial support flows through numerous channels. The International Fellowship of Christians and Jews has raised hundreds of millions of dollars for Israeli causes. Christian groups fund settlement expansion in the West Bank, viewing it as assisting the fulfilment of prophecy. Some support the training of red heifers or the preparation of temple implements, believing these are necessary for end-times events.

The Free Grace Paradox

An intriguing theological tension runs through this political mobilisation. Dispensationalism traditionally emphasises "free grace"—the idea that salvation comes through simple mental assent to Christ's deity and resurrection, not through works or ethical behaviour. This doctrine, taken to its logical conclusion, should produce political quietism: if salvation is purely a matter of belief, why engage in earthly political struggles?

Yet pop-dispensationalist leaders like John Hagee, Jerry Falwell, and Tim LaHaye used the same eschatological framework to demand aggressive political action. The mechanism that resolves this paradox is the transformation of political support for Israel into a test of national faithfulness rather than individual salvation. While individuals might be saved by grace alone, nations receive God's blessing or curse based on their treatment of Israel, per the interpretation of Genesis 12:3. Supporting Israel becomes not a work necessary for personal salvation but a collective devotional act that determines America's national fate.

This differs from crusading, where violence was explicitly penitential—taking up the cross could remit sins and even guarantee salvation if one died in battle. Modern Christian Zionism achieves similar political mobilisation through a different theological mechanism: not individual penance but collective prosperity theology. As Hagee teaches, America's economic health, military security, and divine blessing depend on unwavering support for Israel. Criticism of Israeli policy doesn't just risk personal unfaithfulness; it invites national judgment. Foreign policy thereby becomes a form of collective worship, and political positions about settlements or annexation become tests of whether America will be blessed or cursed by God.

Critically, this theologisation extends to silencing dissent, including from Palestinian Christians. When Palestinian believers express concern about land confiscation, military occupation, or settlement expansion, they are often dismissed by Western Christian Zionists as compromised by "replacement theology" or insufficiently biblical. Their lived experience becomes subordinate to Western eschatological frameworks.

The 2009 Kairos Palestine document, written by leading Palestinian Christian leaders, directly addressed this dynamic: "We know that certain theologians in the West try to attach a biblical and theological legitimacy to the infringement of our rights. Thus, the promises, according to their interpretation, have become a menace to our very existence. The 'good news' in the Gospel itself has become 'a harbinger of death' for us."[^19] These are not marginal voices but include direct descendants of the earliest church, maintaining Christian presence in the Holy Land for two millennia.

As scholars Terence Donaldson and Stephen Sizer observe, this creates a tragic irony: dispensationalism's "strong, and at times fanatical, support for present-day Israel" comes "sadly with little thought given to its corollary of oppression and injustice toward Palestinians who are equally loved by God, many of whom are our brothers and sisters in Christ."[^20] Faithful Palestinian Christians who question whether Genesis 15 mandates support for contemporary settlement policy find themselves accused of rejecting Scripture itself, while their concerns about "home demolitions, theft of water and unreasonable water restrictions for Palestinians, land confiscation, and checkpoints limiting freedom of movement" are treated as theological problems rather than legitimate ethical concerns.[^21]

[^19]: Kairos Palestine 2009, quoted in Donaldson and Sizer, "Who Is Israel?," 86.

[^20]: Donaldson and Sizer, "Who Is Israel?," 49.

[^21]: Donaldson and Sizer, "Who Is Israel?," 51-52.

This creates a peculiar situation: political positions about borders, security policy, settlements, and military action are elevated to the status of doctrinal orthodoxy. To question whether the 1967 borders reflect God's will, or whether settlement expansion serves biblical prophecy, or whether unconditional support for any nation-state is theologically sound, risks being labelled as anti-Israel or, worse, as opposing God's purposes.

The political consequences are substantial. As Lee Marsden documents in his study of the Christian Right and U.S. foreign policy, Christian Zionists have become a powerful force in American politics, working to ensure that "US foreign policy in the Middle East" promotes what they view as biblical obligations toward Israel.[^22] This influence extends beyond electoral politics into policy formation, with Christian Zionist leaders gaining regular access to decision-makers and using "their sermons, lobbying, media campaigns, publications and broadcasting" to "provide support for an aggressive US militarism and unequivocal support for Israel."[^23] The result is that theological convictions about prophecy and covenant shape actual foreign policy decisions affecting millions of people.

[^22]: Lee Marsden, For God's Sake: The Christian Right and US Foreign Policy (London: Zed Books, 2008), 189.

[^23]: Marsden, For God's Sake, 232.

The Structural Parallels

The comparison between Crusader theology and contemporary Christian Zionism reveals four striking structural parallels.

First, both treat contested geopolitical realities as theological certainties. The Crusades reframed the Muslim presence in the Levant—the product of centuries of complex history, conquest, and cultural development—as a simple theological problem requiring a theological solution. Christian Zionism today treats the Israeli-Palestinian conflict—itself the product of competing nationalisms, colonial legacies, displacement, and legitimate competing claims—as a straightforward matter of biblical prophecy fulfilment. In both cases, messy political realities are flattened into theological absolutes.

This isn't to say that theology has no place in political reflection. Christians have always and rightly brought their convictions to bear on questions of justice, peace, and the common good. But there's a crucial difference between letting theology inform political judgement and treating political positions as themselves matters of revealed truth. The former permits disagreement among faithful believers; the latter forecloses it.

Second, both sanctify specific territory in ways that supersede other theological and ethical considerations. For the Crusaders, Jerusalem's status as the site of Christ's death and resurrection transformed it into something more than a city—it became a theological necessity, worth any amount of bloodshed to control. Similarly, for many Christian Zionists, the land of Israel possesses intrinsic theological significance that overrides questions about how it is governed, who lives there, or what justice requires for its inhabitants.

This creates what might be called "sacred geography"—the notion that certain places carry theological weight that outweighs ordinary moral considerations. When land becomes not just important but cosmologically significant, normal ethical reasoning about proportionality, justice for all parties, and peaceful coexistence can be dismissed as insufficiently spiritual or as failing to grasp God's purposes.

Third, both delegitimise dissent by recasting it as unfaithfulness. Just as Crusader critics were marginalised as lacking faith, Christians today who question the theological necessity of supporting Israeli policies often find themselves accused of replacement theology, antisemitism, or rejecting biblical authority. The mechanism is similar: by theologising the political position, disagreement becomes not merely a different prudential judgement but a spiritual failure.

This is particularly evident in how Christian Zionist discourse treats Palestinian Christians. These believers—direct descendants of the earliest church, maintaining Christian presence in the Holy Land for two millennia—raise concerns about home demolitions, land confiscation, and restricted movement. But because their concerns conflict with the eschatological framework, they are often dismissed as theologically compromised. The irony is profound: Western Christians, geographically and culturally distant from the situation, claim to better understand God's will for the land than indigenous Christians living under occupation.

Fourth, both risk a form of idolatry by elevating nation and territory to compete with Christ. The First Crusade's chroniclers described Crusaders weeping with joy upon seeing Jerusalem, kissing its walls, and treating its very stones as holy. Modern Christian Zionism can display similar veneration—not of Christ, but of the nation-state of Israel. When Christians claim that blessing Israel is the key to blessing, or that God judges nations based on their stance toward Israeli policies, or that the restoration of Israel is more significant than the resurrection of Christ (as some dispensationalists have suggested), we've crossed into dangerous territory.

The New Testament insists that in Christ, the dividing wall between Jew and Gentile has been broken down (Ephesians 2:14), that believers' citizenship is in heaven (Philippians 3:20), and that there is neither Jew nor Greek in Christ (Galatians 3:28). When theological systems place ethnic Israel at the centre of God's purposes in ways that marginalise the centrality of Christ and the church, something has gone awry. This doesn't mean God has abandoned the Jewish people—Romans 9-11 emphatically denies this—but it does mean that Christian theology must be fundamentally Christocentric, not nation-centric.

What's Different and Why It Matters

Lest this analysis be misread as simple equation, it's essential to acknowledge crucial differences between the Crusades and contemporary Christian Zionism.

The Crusades were wars of conquest, explicitly military campaigns launched by popes and kings. Christian Zionism, while politically influential, is primarily a support movement for an existing nation-state. Most Christian Zionists are not advocating for Christians to personally take up arms and invade territory (though some do support Israeli military action theologically). The agency and the violence are different.

Moreover, the state of Israel exists within a framework of international law, with recognised borders (however contested), membership in international bodies, and democratic institutions. The Crusader kingdoms were imposed by force and maintained by military occupation with no pretence of local consent. Modern Israel, whatever one thinks of its policies, emerged from a complex historical process involving both Jewish agency and international recognition, not simply foreign invasion.

There are also legitimate, non-theological reasons for Christians to care about Israel. The historical connection between Christianity and Judaism, the horror of the Holocaust and Christian complicity in antisemitism, the existence of Christian communities in Israel, concerns about religious freedom and democratic governance in the region—all these provide grounds for Christian interest and engagement that don't depend on eschatological frameworks or land promises.

Furthermore, supporting Israel's right to exist securely is not equivalent to endorsing specific policies. One can believe that Jewish people deserve a homeland after centuries of persecution without believing that West Bank settlements fulfil biblical prophecy. One can care about Israeli security without treating every military operation as divinely ordained. The problem arises when these distinctions collapse, when any criticism of policy is treated as opposition to existence, when prudential disagreements about governance become matters of theological orthodoxy.

These differences matter because the argument here is not "Christian Zionism equals the Crusades" but rather "Christian Zionism employs a similar structure of theological reasoning that proved catastrophic in the Crusades." It's a warning about a pattern, not a claim of identity.

The Danger of Theological Determinism

The core problem in both cases is theological determinism applied to politics—the insistence that God has revealed not just general principles but specific political outcomes, territorial arrangements, and policy positions. This creates several interrelated dangers.

First, it confuses human interpretation with divine revelation. The Bible requires interpretation; faithful Christians have always disagreed about what texts mean and how they apply. When we claim that our interpretation of Genesis 15 or Zechariah 12 yields certainty about modern borders or settlement policy, we've stopped doing theology and started doing ideology. We've mistaken our reading for God's speaking.

Second, it forecloses the possibility of learning from circumstances or changing positions based on new information. If God has mandated a particular outcome, then evidence of harm, failed policies, or unintended consequences becomes irrelevant. When settlers bulldoze Palestinian olive groves, when Israeli forces kill civilians, when policies create humanitarian crises—if these are all part of God's prophetic plan, then moral objection becomes impiety. The theology functions as moral anaesthetic.

Third, it weaponises Scripture against the vulnerable. When powerful nations or movements claim divine sanction, the weak suffer. Palestinian Christians under occupation are told their suffering serves God's purposes. Displaced families are informed that their loss fulfils prophecy. This is not merely insensitive; it's a form of theological violence, using God's name to justify harm.

Fourth, it corrupts Christian witness. When the watching world sees Christians prioritising political support for a nation-state over concern for all people made in God's image, when they see theology deployed to justify dispossession, when they see Jesus's followers treating some people as means to eschatological ends, the gospel itself becomes discredited. We become, as Palestinian theologian Mitri Raheb has noted, "a stumbling block" rather than a witness.

Towards Epistemic Humility

There is an alternative: epistemic humility about our political judgements, even when informed by our theology. We can hold convictions without claiming divine certainty. We can support policies without theologising them. We can care deeply about outcomes while acknowledging that faithful Christians may disagree about means.

This doesn't mean theological reasoning has no place in political reflection. Christians rightly bring biblical principles about justice, peace, care for the vulnerable, and human dignity to bear on every situation, including the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. But there's a profound difference between saying "justice requires X" (a theological claim about principles) and saying "God requires this specific political outcome" (a claim to know God's will about contingent historical arrangements).

Consider an analogy: Christians generally agree that caring for the poor is biblically mandated. But we disagree—often sharply—about whether this requires progressive taxation, private charity, universal basic income, or some combination thereof. We don't treat these prudential disagreements as heresy because we recognise them as applications of principles to complex situations, requiring judgement, wisdom, and openness to evidence. Why should Israel-Palestine be different?

A humble approach would acknowledge uncertainty. It would say: "I believe supporting Israel's security is important for these reasons, but I recognise other faithful Christians weigh the considerations differently." It would permit Palestinian Christians to be heard as full members of the body of Christ, not theological problems to be explained away. It would allow space for criticising policies—settlement expansion, home demolitions, disproportionate force—without such criticism being construed as opposing God.

It would also take seriously the possibility that our eschatological frameworks might be wrong. Dispensationalism is, historically speaking, a recent innovation. For most of Christian history, the church read the land promises as fulfilled in Christ or as applying to the new creation, not as mandating support for a future nation-state. Maybe that older reading was correct. Maybe our confident assertions about God's prophetic timetable reflect more about American evangelical culture than about scriptural necessity.

Conclusion

The Crusades stand as one of Christian history's great cautionary tales—a reminder of what happens when political ambitions dress themselves in theological certainty, when land becomes more sacred than people, when dissent becomes heresy. The wreckage they left—the slaughter, the bitterness, the poisoned relations—should haunt us still. Even the celebrated historian Steven Runciman condemned the Crusades as "one long act of intolerance in the name of God which is the sin against the Holy Ghost."[^11]

[^11]: Quoted in Tyerman, Fighting for Christendom, 16.

Contemporary Christian Zionism, particularly in its more deterministic forms, employs a similar theological architecture. It transforms political positions into divine mandates, treats contested territory as cosmologically significant, and struggles to permit faithful disagreement. The outcomes differ in scale and character from the Crusades, but the pattern of reasoning is recognisably similar. And patterns matter. As Tyerman notes, crusading "helped define a rancid aspect of a persecuting mentality" in its treatment of Jews, heretics, and dissenters.[^12] When theology becomes the justification for marginalising or harming the vulnerable, we repeat destructive patterns regardless of the specific context.

[^12]: Tyerman, Fighting for Christendom, 122.

This doesn't mean Christians should be indifferent to Israel or Jewish-Christian relations. It means our engagement should be characterised by humility rather than certainty, by concern for all people rather than privileging one group, by openness to correction rather than defensive absolutism. We can care about Israel's security without claiming God has revealed his will about settlement policy. We can hope for peace without asserting we know the borders God requires. We can support Jewish flourishing without theologising every Israeli government action.

The fundamental question is this: Will we let our political preferences be informed by our theology, or will we baptise our political preferences as theology? The former is faithful engagement; the latter is the error the Crusaders made, with catastrophic results.

If we've learned anything from church history, it should be caution about claiming too much certainty regarding God's geopolitical preferences. The God who told us his kingdom is not of this world, who calls us to love enemies and pray for persecutors, who died at the hands of a Roman-Jewish collaboration rather than calling down legions of angels—this God is poorly served by theologies that make political arrangements ultimate.

Better to hold our political judgements with open hands, subject always to correction by Scripture, by the witness of the global church (including Palestinian believers), and by the evidence before us. Better to prioritise faithfulness to Christ over certainty about borders. Better to risk being wrong about eschatology than to risk becoming stumbling blocks to the gospel.

The holy land need not become holy war, whether in the 11th century or the 21st. But preventing that requires recognising the pattern when it appears and choosing a different path—one marked by humility, by care for all God's image-bearers, and by refusing to mistake our political judgements for divine revelation.

The story of the Crusades retains "the power to excite, appal, and disturb" precisely because it reflects enduring human temptations.[^13] The temptation to claim divine sanction for our political projects. The temptation to make geography sacred and thereby justify violence. The temptation to silence dissent by calling it heresy. These patterns recur across centuries because they appeal to something deep in religious communities: the desire for certainty, for enemies clearly identified, for God unambiguously on our side.

Understanding crusading—"for itself and to explain its survival"—remains "an urgent contemporary task."[^14] Not because we're doomed to repeat it exactly, but because studying how the Crusades were constructed and remembered teaches us how cultures construct and remember violence to replicate it in the present. The Crusades weren't inevitable; they were made through specific theological moves, narrative framings, and institutional developments. Understanding those mechanisms helps us recognise when similar patterns emerge in our own time.

Christian Zionism is only one modern manifestation. The pattern appears wherever Christians claim too much certainty about God's geopolitical preferences, wherever political borders become divine boundaries, wherever supporting specific policies becomes a test of faithfulness. The theological architecture—transforming politics into theology, sacralising territory, delegitimising dissent—continues to tempt us precisely because it provides enormous energy and clarity for political movements.

Think of theologically deterministic politics as a theological fire: it provides immense warmth and energy for a movement, drawing people together around shared certainty and cosmic purpose. But it is fundamentally untamed. Once a political position is ignited as a divine mandate, the fire consumes the possibility of rational negotiation, burns away nuance and complexity, and scorches anyone who attempts to stand on the "wrong" side of the flames. The fire cannot be moderated or banked; it can only burn or be extinguished. This is why theological determinism is so dangerous even when deployed for causes that seem righteous: it transforms politics into warfare and disagreement into heresy, making peaceful coexistence progressively impossible.

[^13]: Tyerman, Fighting for Christendom, vii.

[^14]: Tyerman, Fighting for Christendom, 7.

[Word count: 4,497]